One more round of site theme ideas. I think I might really like this round. Do folks like these more or less then the last batch? I did not fill in all the content for these, just a few boxes and headings to give a sense of the concept. Each of them would take a bit more work. These are generated out of cut up shots from mega man, so I would be mushing and chewing on those original images a bit, but I thought I would share these.

Category: Education

-

Darwin, History, and Visualizations

Two weeks ago our Creating History in New Media class had a great chance to chat with historian David Staley about his book Computers Visualization and History and Scott McCloud‘s book Understanding Comics. New media provides some exciting places to take conversations about visualizations in history, but one of my other take-a-ways from the conversation was that there are a lot of places to talk about historical visualizations in old media.

I know that I said it’s not about pictures, but for those of you interested in pictures there are some neat projects that you can look to. To (quite literally) illustrate the point, here are a few examples of some of some dead tree picture based visualizations.

Children’s Picture Books

Below is a shot from Peter Sis’ The Tree of Life: Charles Darwin. Each page of the book places the primary content of the story in the center circle and frames. The picture below isn’t the best example but it does a good job demonstrating the way the side stories leaf into the center image to express different parts of a related story. Over the last thirty years or so critics and artists have developed several different works that explore how picture books work. Folks interested visually communicating history might do well to borrow from their work.

Science Comics

As I mentioned, alongside Computers Visualization and History our class also read Understanding Comics. It is worth mentioning that comics themselves are becoming a compelling medium for visually communicating history. In my own area of interest, the History of Science, Jim Ottaviani and Jay Hosler have developed some fantastic examples of what you can do with comics. Below is a page from a great book about Darwin’s ear ticks by Hosler.

Photos of Legos With Currency

Ok it doesn’t really fit, but it’s awesome-ness outweighed its misfit-ness, so here it is.

So, why have I pulled together these images? To demonstrate that there are already communities of comic and picture book artists interested in presenting historical information to young and old alike, many of who are doing a bang up job. There is enough material out there to just focus in on a single figure like darwin and see different examples from these fields. If historians want to think more about developing picture based visualizations they would do well to try folding in insights form these different communities.

-

£very1 c4n |_rn 2 ©ode (Everyone Learn to Code)

How Do We Get The Necessary Self Efficacy To Code

original image from Capture Queen http://flickr.com/photos/uaeincredible/ For all the talk of read/write culture and how digital media has blurred the lines between producer and consumer, (or even prosumer if you like making up words) there is much less conversation about learning to write code. In my experience these conversations happen, almost exclusively, about tools that use graphical interfaces and wysiwyg editors for content creation. I think Marc Prensky is right in suggesting that programing itself is a new literacy, or even better yet I would suggest it’s really a deeper conception of digital literacy. In calling something a literacy were making it a fundamental, and I think the database driven programmatic nature of new media requires that folks start to take a proactive approach to making programing a part of our general education approach.

Before we can even really talk about that goal however there is something I think we need to figure out first. Many people don’t think they have it in them to work with code. I have seen people who are masters at manipulating things in complicated programs with graphical interfaces. Folks that can do amazing things in Final Cut, people who have no trouble troubleshooting issues that arise with their operating systems, but who power down when anything from HTML to C++ is mentioned. I frequently hear, “I can’t do that”, “I’m not a coder” or similar statements rooted in idenity, afinity and self-efficacy.

It is important to note that I say this, not as a confident coder but as someone who has gotten over his own fears about working through hunks of code. The things I have done, editing and tweaking Omeka and WordPress themes, hacking CSL‘s to get customized export from Zotero making a minor fix to one of Zotero’s translators, all required no training in JavaScript, or XML. Once I was comfortable with skipping chunks of stuff I did not understand I was generally able to get these things to do what I wanted to do. In these cases at least, the biggest barrier was my own lack of self efficacy with the idea of doing things with code.

There are a lot of great ways learn to code. (For a good list check out Karin Dalziel’s post, its directed at librarians but there are some great resources there.) However, I have not seen much work focusing on how we can get people over the paralysis that comes from the belief that it writing code is outside their grasp. To really break down these barriers, and get more folks to a deeper level of digital literacy, I think we need to know more about where that fear comes from and start developing stratigies for overcomming it.

-

Disney Goes Atomic

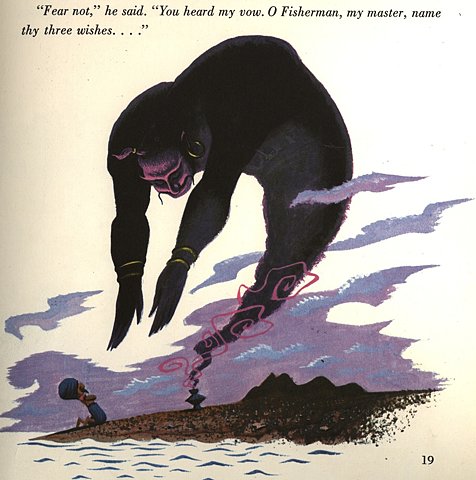

In 1956 Disney published Our Friend the Atom as a compliment to a film and exhibition by the same name. The book uses a fable of a fishermen and a genie to explain the relation between people and atomic science, and the book strangely simultaneously offers much scarier visuals of the destructive power of atomic science than one would expect children of the fifties would have been exposed to but still manages to present a Utopian view of the future potential of the technology.

The analogy of the genie and fisherman forms the central framework for the book. The fisherman discovers a lamp which he then pries open.

With that a very menacing genie emerges from the lamp. Not the humorous and benevolent genie Disney gave my generation but a big old nasty genie. Instead of being grateful for his release this genie is quite disgruntled. Once freed he proclaims that “because thou has freed me, thou must die. For I am one of those condemned spirits who long ago disobeyed the word of king Solomon.” The genie then asks the fishermen to “chose how he will die”.

Through some deft trickery the fishermen convinces the genie to get back into his lamp, at which point the fishermen decides to throw the lamp back into the sea. The genie pleads with him to free him once again offering him three wishes.

On the next page the story is mapped on to the history of the atom. This page promises to explain “how the atomic vessel was discovered, how man learned of its many marvelous secrets, how the atomic Genie was liberated, and what we must do to make him our friend and servant.” I highly recommend right clicking on the image below to see the whole thing. The way Disney maps the story of the genie directly onto the history of atomic science is both bizarre and fascinating.In strange form the dark imagery of the first encounter with the genie is ever present throughout the story. While the book is ultimately about human progress via technology these dark images keep reoccurring.

Ultimately children learn that humanity has somehow tricked the atom in just the same way that the fisherman tricked the genie. For this they are granted three wishes by the atom. The atomic genie will give us power, food and health, and ultimately that power, food and health will give the world peace.

-

1934: A Better Time to Be A Girl Interested in Science?

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century Nature Study was the cutting edge approach in American science education. Educational scholars claimed students should “study nature, not books” and education took on a much more practical bent. Some scholars have noted that this approach to science education was much more gender inclusive, that nature study invited more women and girls into the sphere of science. The following images from Science Stories, a 1934 American science textbook, would seem to support the argument that nature study was more inviting to girls. In the past fifty years various science textbooks have come under scrutiny for including only pictures of boys and men in the book’s illustrations. Take a look at the following set of pictures from the book, these representative selections show boys and girls working together, something later books have largely failed to do. If this book is at all indicative of other texts and approaches from the time it would seem to be incontrovertible that Nature Study brought about a much more gender neutral approach for presenting science to children.

Science Stories follows a group of students and their teacher through the four seasons. Almost every page includes a picture, and almost every picture that includes a boy includes a girl as well. In the picture above we can see students in Autumn looking at leaves and twigs. Many of the stories focus on students activities outside. It is also worth mentioning that the science teacher is female.

The gender equity in the pictures follows the students back into the classroom. Many images like the one above show boys and girls workign together, in this case on some sort of diorama. Almost every single image shows boys and girls working together.

Beyond dioramas the gender equity extended to working with scientific equipment (see above) and children working on their homework.

Throughout the book boys and girls work together, collaborating and exploring their natural world. Aside from being a pleasant read, filled with beautiful illustrations, the Science Stories book is an interesting example of a gender inclusive curriculum. While we like to think that science and science education have become increasingly open to women these images, work like Kimberly Tolley’s Science Education of American Girls and explorations of the nature study movement suggests otherwise. It seems that the history of gender in science and science education is much more dynamic than we previously thought.

-

Suprises in Early Children’s Books About Evolution

From the Scopes to Dover Area School District teaching evolution continues to be a perennial sore spot in American education. More often than not textbooks are at the center of these controversies. There are several excellent studies of the history of Evolution in text books. In Trial and Error Edward Larson argued that the scopes trial exacerbated “Existing restrictions and fears of further controversy” in teaching about evolution and ultimately “led commercial publishers to de-emphasize evolution in their high school textbooks.” In a similar vein sociologist Gerald Skoog found after the Scopes Trial “The most sensitive evolutionary topics, including the origin of life and the evolution of man, rarely appeared at all” in textbooks “Less than half of the texts even used the word “evolution”. ” Curiously, the the Scopes trial seems to have had the opposite effect on children’s books about evolution. Books directed at a much younger audience. The first time the Children’s Catalog, a guide to Children’s books for librarians, listed books under the heading “Evolution” was the year after the scopes trial.

William Maxwell Reed‘s 1929 book The Earth for Sam is one of the first American children’s books to engage with evolution. ( I have found six other books from the same time period) In an example endemic of all these children’s evolution books Reed claims; “We saw life become a cell, then a group of cells. In turn there have appeared before us the fish, the amphibian, the reptile, and the mammal.” He goes on to address human decent directly; “Finally from among the mammals there appeared the primates and from among the primates the European white primates who founded the British Empire and the United States of America.” While the textbooks were becoming conservative, often not even mentioning the word evolution, children’s books emerged boldly asserting an ancient earth, and the decent of man.

I think this example may be a fruitful one for considering the relationship between children’s books and textbooks more generally. Every student gets the textbook. I think this may well make them a much more conservative medium. In contrast children’s books can be marketed to smaller niche groups of parents and librarians; allowing them to encompass a broader range of perspectives. Because Historians and Sociologists considering the place of evolution in the history of American education have focused on textbooks they have missed some nuance in this history. Instead of Scopes forcing education to become much more conservative, the trial appears to have had a polarizing effect. Simultaneously forcing the conservative medium of textbooks to cut out evolution and in parallel creating enough public interest in the topic to substantiate a new genre of children’s literature on the topic.

Pictures from William Maxwell Reed, The Earth for Sam: The Story of Mountains, Rivers, Dinosaurs and Men. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1929.